21

Videos, Music, Poems, General discussions / Indrajala (Sanskrit: इन्द्रजाल) or "Indra's Net"

« Last post by Yeshu on June 07, 2024, 08:54:51 PM »According to Rajiv Malhotra, the earliest reference to a net belonging to Indra is in the Atharva Veda (c. 1000 BCE).[14] Verse 8.8.6. says:

And verse 8.8.8. says:

The net was one of the weapons of the sky-god Indra, used to snare and entangle enemies.[17] The net also signifies magic or illusion.[18] According to Teun Goudriaan, Indra is conceived in the Rig Veda as a great magician, tricking his enemies with their own weapons, thereby continuing human life and prosperity on earth.[19] Indra became associated with earthly magic, as reflected in the term indrajal, "Indra's Net", the name given to the occult practices magicians.[19] According to Goudriaan, the term indrajalam seems to originate in verse 8.8.8 from the Atharva Veda, of which Goudriaan gives a different translation:[20]

According to Goudriaan, The net being referred to here ...was characterized there as the antariksa-, the intermediate space between heaven and earth, while the directions of the sky were the net's sticks (dandah) by means of which it was fastened to the earth. With this net Indra conquered all his enemies.[20]

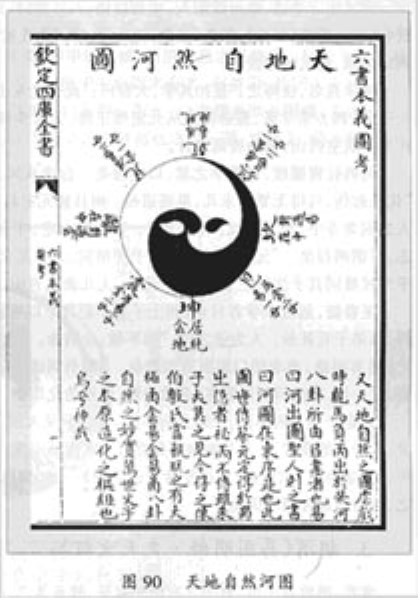

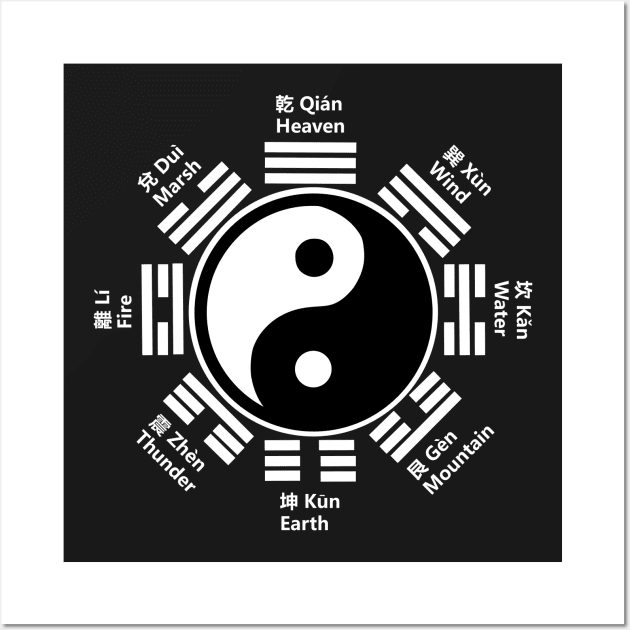

"Indra's net" is an infinitely large net owned by the Vedic deva Indra, which hangs over his palace on Mount Meru, the axis mundi of Buddhist and Hindu cosmology. In East Asian Buddhism, Indra's net is considered as having a multifaceted jewel at each vertex, with each jewel being reflected in all of the other jewels.[4] In the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, which follows the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra, the image of "Indra's net" is used to describe the interconnectedness or "perfect interfusion" (yuánróng, 圓融) of all phenomena in the universe.[4][5]

Francis H. Cook describes Indra's net thus:

Far away in the heavenly abode of the great god Indra, there is a wonderful net which has been hung by some cunning artificer in such a manner that it stretches out infinitely in all directions. In accordance with the extravagant tastes of deities, the artificer has hung a single glittering jewel in each "eye" of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number. There hang the jewels, glittering "like" stars in the first magnitude, a wonderful sight to behold. If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring.[6]

The Buddha in the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra's 30th book states a similar idea:

Book 30 of the Buddhāvataṃsaka is named "The Incalculable" because it focuses on the idea of the infinitude of the universe and as Thomas Cleary notes, concludes that "the cosmos is unutterably infinite, and hence so is the total scope and detail of knowledge and activity of enlightenment."[8]

In another part of the Buddhāvataṃsaka sutra, the actual metaphor of "Indra's Net" is used to refer to the all phenomena in the dharmadhātu ("dharma realm", ultimate reality, the ultimate principle, Chinese: 法界中):

They [Buddhas] know all phenomena come from interdependent origination.

They know all world systems exhaustively. They know all the different phenomena in all worlds, interrelated in Indra's net.[9]

The metaphor of Indra's net of jewels plays an essential role in the metaphysics of the Chinese Buddhist Huayan school,[10] where it is used to describe the interpenetration or "perfect interfusion" (Chinese: yuánróng, 圓融) of microcosmos and macrocosmos, as well as the interfusion of all dharmas (phenomena) in the entire universe.[5] According to Bryan Van Norden, in the Huayan tradition, Indra's net is "adopted as a metaphor for the manner in which each thing that exists is dependent for both its existence and its identity upon every other thing that exists."[11]

The Huayan text entitled "Calming and Contemplation in the Five Teachings of Huayan" (Huayan wujiao zhiguan 華嚴五教止觀, T1867) attributed to the first Huayan patriarch Dushun (557–640) gives an extended overview of this concept:

The manner in which all dharmas interpenetrate is like an imperial net of celestial jewels extending in all directions infinitely, without limit. … As for the imperial net of heavenly jewels, it is known as Indra’s Net, a net which is made entirely of jewels. Because of the clarity of the jewels, they are all reflected in and enter into each other, ad infinitum. Within each jewel, simultaneously, is reflected the whole net. Ultimately, nothing comes or goes. If we now turn to the southwest, we can pick one particular jewel and examine it closely. This individual jewel can immediately reflect the image of every other jewel.

As is the case with this jewel, this is furthermore the case with all the rest of the jewels–each and every jewel simultaneously and immediately reflects each and every other jewel, ad infinitum. The image of each of these limitless jewels is within one jewel, appearing brilliantly. None of the other jewels interfere with this. When one sits within one jewel, one is simultaneously sitting in all the infinite jewels in all ten directions. How is this so? Because within each jewel are present all jewels. If all jewels are present within each jewel, it is also the case that if you sit in one jewel you sit in all jewels at the same time. The inverse is also understood in the same way. Just as one goes into one jewel and thus enters every other jewel while never leaving this one jewel, so too one enters any jewel while never leaving this particular jewel.[12]

The Huayan Patriarch Fazang (643–712) used the golden statue of a lion to demonstrate the Huayan vision of interpenetration to empress Wu:[13]

In each of the lion's eyes, in its ears, limbs, and so forth, down to each and every single hair, there is a golden lion. All the lions embraced by each and every hair simultaneously and instantaneously enter into one single hair. Thus, in each and every hair there are an infinite number of lions... The progression is infinite, like the jewels of Celestial Lord Indra's Net: a realm-embracing-realm ad infinitum is thus established, and is called the realm of Indra's Net.[13]

Indrajala (Sanskrit: इन्द्रजाल) is a Sanskrit word common to most Indian languages that means Indra's net, magic, deception, fraud, illusion, conjuring, jugglery, sorcery etc.[1]

In Hinduism the first creator of maya in this universe was Indra. The term Indrajala was used instead of maya in the ancient days. Since Indra represents God and God's creation of this universe can be considered a magical act, this whole world is Indrajala (a net of Indra), an illusion.[2]

In a similar fashion, the human magician applies the magic called Indrajala in imitation of his divine forerunners, and thus spreads his net of maya over those he chooses as the object of his manipulations. He creates something before the eyes of the spectators that does not really exist, or only exist in the spectators’ minds as a result of his skill.

If one confines Indrajala to its stricter sense of illusory appearances created for the public, it is understandable that this activity was apt to become an image for the great illusion to hold ignorant mankind in its grasp. According to the Advaita philosophers there is no difference between avidya (ignorance) and moha ("delusion") as factors that lead to human bondage.

Magic and Religion sometimes go together. The most important source for the knowledge of Vedic magic is Atharvaveda. Those mantras of the Vedas that are meant for shanti, for allaying fears and evils, for greater welfare and for extension of life, etc., are called pratyangiramantrah or atharvanah, but those meant for harming others, i.e., abhichara, are called angiramantrah or angirasah.

Hindu belief contends that the fundamental power of Brahman—which penetrates existence and is neutral by itself—can be used by qualified specialists for good or evil ends.[3] To scare the enemy is the aim of Indrajala.[4]

Kamandaka and the Puranas include Upeksha, Maya and Indrajala as sub-methods of diplomacy. Indrajala is the use of stratagems for victory over the enemy and according to Kautilya it comes under Bheda.[5]

Danu (Sanskrit: दनु, IAST: Danu) is a Hindu primordial goddess. She is mentioned in the Rigveda to be the mother of the eponymous race known as the danavas. The word Danu described the primeval waters that this deity perhaps embodied. In later Hinduism, she is described as the daughter of the Prajapati Daksha and his spouse Panchajani, and the consort of the sage Kashyapa.[1]

As a word for "rain" or "liquid", dānu is compared to Avestan dānu, "river", and further to river names like Don, Danube, Dnieper, Dniestr, etc. There is also a Danu river in Nepal. The "liquid" word is mostly neutral, but appears as feminine in RV 1.54.

In the Rigveda (I.32.9), she is identified as the mother of Vritra, the asura DRAGON slain by Indra.[2]

In the Padma Purana, the children of Danu are described:

From Kaśyapa, Danu obtained a hundred sons proud of boons. Among them Vipracitti, of great power, was the chief. (Others were) Dviraṣṭamūrdhā, Śakuni, Śaṅkuśirodhara, Ayomukha, Śambara, Kapila, Vāmana, Marīci, Māgadha, and Hari. Gajaśiras, Nidrādhara, Ketu, Ketuvīrya Taśakratu, Indramitragraha, Vrajanābha, Ekavastra, Mahābāhu, Vajrākṣa, Tāraka, Asiloman, Puloman, Vikurvāṇa, Mahāpura, Svarbhānu, and Vṛṣaparvan—these and others were also Danu’s sons. Suprabhā was Svarbhānu’s daughter, and Śacī was the daughter of Puloman.

— Padma Purana, Book 1, Chapter 6

In the Brahmanda Purana, it is stated that while Aditi is habitually righteous, and Diti was habitually strong, Danu habitually practices maya.[4]

Danu was struck by Indra's thunderbolt after hearing him kill her son Vritra.[5]

Quote

Vast indeed is the tactical net of great Indra, mighty of action and tempestuous of great speed. By that net, O Indra, pounce upon all the enemies so that none of the enemies may escape the arrest and punishment.[15]

And verse 8.8.8. says:

Quote

This great world is the power net of mighty Indra, greater than the great. By that Indra-net of boundless reach, I hold all those enemies with the dark cover of vision, mind and senses.[16]

The net was one of the weapons of the sky-god Indra, used to snare and entangle enemies.[17] The net also signifies magic or illusion.[18] According to Teun Goudriaan, Indra is conceived in the Rig Veda as a great magician, tricking his enemies with their own weapons, thereby continuing human life and prosperity on earth.[19] Indra became associated with earthly magic, as reflected in the term indrajal, "Indra's Net", the name given to the occult practices magicians.[19] According to Goudriaan, the term indrajalam seems to originate in verse 8.8.8 from the Atharva Veda, of which Goudriaan gives a different translation:[20]

Quote

This world was the net of the great Sakra (Indra), of mighty size; by means of this net of Indra I envelop all those people with darkness.[20]

According to Goudriaan, The net being referred to here ...was characterized there as the antariksa-, the intermediate space between heaven and earth, while the directions of the sky were the net's sticks (dandah) by means of which it was fastened to the earth. With this net Indra conquered all his enemies.[20]

"Indra's net" is an infinitely large net owned by the Vedic deva Indra, which hangs over his palace on Mount Meru, the axis mundi of Buddhist and Hindu cosmology. In East Asian Buddhism, Indra's net is considered as having a multifaceted jewel at each vertex, with each jewel being reflected in all of the other jewels.[4] In the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, which follows the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra, the image of "Indra's net" is used to describe the interconnectedness or "perfect interfusion" (yuánróng, 圓融) of all phenomena in the universe.[4][5]

Francis H. Cook describes Indra's net thus:

Far away in the heavenly abode of the great god Indra, there is a wonderful net which has been hung by some cunning artificer in such a manner that it stretches out infinitely in all directions. In accordance with the extravagant tastes of deities, the artificer has hung a single glittering jewel in each "eye" of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number. There hang the jewels, glittering "like" stars in the first magnitude, a wonderful sight to behold. If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring.[6]

The Buddha in the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra's 30th book states a similar idea:

Quote

If untold Buddha-lands are reduced to atoms,

In one atom are untold lands, and as in one, so in each.

The atoms to which these Buddha-lands are reduced in an instant are unspeakable,

And so are the atoms of continuous reduction moment to moment, going on for untold eons;

These atoms contain lands unspeakably many, and the atoms in these lands are even harder to tell of.[7]

Book 30 of the Buddhāvataṃsaka is named "The Incalculable" because it focuses on the idea of the infinitude of the universe and as Thomas Cleary notes, concludes that "the cosmos is unutterably infinite, and hence so is the total scope and detail of knowledge and activity of enlightenment."[8]

In another part of the Buddhāvataṃsaka sutra, the actual metaphor of "Indra's Net" is used to refer to the all phenomena in the dharmadhātu ("dharma realm", ultimate reality, the ultimate principle, Chinese: 法界中):

They [Buddhas] know all phenomena come from interdependent origination.

They know all world systems exhaustively. They know all the different phenomena in all worlds, interrelated in Indra's net.[9]

The metaphor of Indra's net of jewels plays an essential role in the metaphysics of the Chinese Buddhist Huayan school,[10] where it is used to describe the interpenetration or "perfect interfusion" (Chinese: yuánróng, 圓融) of microcosmos and macrocosmos, as well as the interfusion of all dharmas (phenomena) in the entire universe.[5] According to Bryan Van Norden, in the Huayan tradition, Indra's net is "adopted as a metaphor for the manner in which each thing that exists is dependent for both its existence and its identity upon every other thing that exists."[11]

The Huayan text entitled "Calming and Contemplation in the Five Teachings of Huayan" (Huayan wujiao zhiguan 華嚴五教止觀, T1867) attributed to the first Huayan patriarch Dushun (557–640) gives an extended overview of this concept:

The manner in which all dharmas interpenetrate is like an imperial net of celestial jewels extending in all directions infinitely, without limit. … As for the imperial net of heavenly jewels, it is known as Indra’s Net, a net which is made entirely of jewels. Because of the clarity of the jewels, they are all reflected in and enter into each other, ad infinitum. Within each jewel, simultaneously, is reflected the whole net. Ultimately, nothing comes or goes. If we now turn to the southwest, we can pick one particular jewel and examine it closely. This individual jewel can immediately reflect the image of every other jewel.

As is the case with this jewel, this is furthermore the case with all the rest of the jewels–each and every jewel simultaneously and immediately reflects each and every other jewel, ad infinitum. The image of each of these limitless jewels is within one jewel, appearing brilliantly. None of the other jewels interfere with this. When one sits within one jewel, one is simultaneously sitting in all the infinite jewels in all ten directions. How is this so? Because within each jewel are present all jewels. If all jewels are present within each jewel, it is also the case that if you sit in one jewel you sit in all jewels at the same time. The inverse is also understood in the same way. Just as one goes into one jewel and thus enters every other jewel while never leaving this one jewel, so too one enters any jewel while never leaving this particular jewel.[12]

The Huayan Patriarch Fazang (643–712) used the golden statue of a lion to demonstrate the Huayan vision of interpenetration to empress Wu:[13]

In each of the lion's eyes, in its ears, limbs, and so forth, down to each and every single hair, there is a golden lion. All the lions embraced by each and every hair simultaneously and instantaneously enter into one single hair. Thus, in each and every hair there are an infinite number of lions... The progression is infinite, like the jewels of Celestial Lord Indra's Net: a realm-embracing-realm ad infinitum is thus established, and is called the realm of Indra's Net.[13]

Indrajala (Sanskrit: इन्द्रजाल) is a Sanskrit word common to most Indian languages that means Indra's net, magic, deception, fraud, illusion, conjuring, jugglery, sorcery etc.[1]

In Hinduism the first creator of maya in this universe was Indra. The term Indrajala was used instead of maya in the ancient days. Since Indra represents God and God's creation of this universe can be considered a magical act, this whole world is Indrajala (a net of Indra), an illusion.[2]

In a similar fashion, the human magician applies the magic called Indrajala in imitation of his divine forerunners, and thus spreads his net of maya over those he chooses as the object of his manipulations. He creates something before the eyes of the spectators that does not really exist, or only exist in the spectators’ minds as a result of his skill.

If one confines Indrajala to its stricter sense of illusory appearances created for the public, it is understandable that this activity was apt to become an image for the great illusion to hold ignorant mankind in its grasp. According to the Advaita philosophers there is no difference between avidya (ignorance) and moha ("delusion") as factors that lead to human bondage.

Magic and Religion sometimes go together. The most important source for the knowledge of Vedic magic is Atharvaveda. Those mantras of the Vedas that are meant for shanti, for allaying fears and evils, for greater welfare and for extension of life, etc., are called pratyangiramantrah or atharvanah, but those meant for harming others, i.e., abhichara, are called angiramantrah or angirasah.

Hindu belief contends that the fundamental power of Brahman—which penetrates existence and is neutral by itself—can be used by qualified specialists for good or evil ends.[3] To scare the enemy is the aim of Indrajala.[4]

Kamandaka and the Puranas include Upeksha, Maya and Indrajala as sub-methods of diplomacy. Indrajala is the use of stratagems for victory over the enemy and according to Kautilya it comes under Bheda.[5]

Danu (Sanskrit: दनु, IAST: Danu) is a Hindu primordial goddess. She is mentioned in the Rigveda to be the mother of the eponymous race known as the danavas. The word Danu described the primeval waters that this deity perhaps embodied. In later Hinduism, she is described as the daughter of the Prajapati Daksha and his spouse Panchajani, and the consort of the sage Kashyapa.[1]

As a word for "rain" or "liquid", dānu is compared to Avestan dānu, "river", and further to river names like Don, Danube, Dnieper, Dniestr, etc. There is also a Danu river in Nepal. The "liquid" word is mostly neutral, but appears as feminine in RV 1.54.

In the Rigveda (I.32.9), she is identified as the mother of Vritra, the asura DRAGON slain by Indra.[2]

In the Padma Purana, the children of Danu are described:

From Kaśyapa, Danu obtained a hundred sons proud of boons. Among them Vipracitti, of great power, was the chief. (Others were) Dviraṣṭamūrdhā, Śakuni, Śaṅkuśirodhara, Ayomukha, Śambara, Kapila, Vāmana, Marīci, Māgadha, and Hari. Gajaśiras, Nidrādhara, Ketu, Ketuvīrya Taśakratu, Indramitragraha, Vrajanābha, Ekavastra, Mahābāhu, Vajrākṣa, Tāraka, Asiloman, Puloman, Vikurvāṇa, Mahāpura, Svarbhānu, and Vṛṣaparvan—these and others were also Danu’s sons. Suprabhā was Svarbhānu’s daughter, and Śacī was the daughter of Puloman.

— Padma Purana, Book 1, Chapter 6

In the Brahmanda Purana, it is stated that while Aditi is habitually righteous, and Diti was habitually strong, Danu habitually practices maya.[4]

Danu was struck by Indra's thunderbolt after hearing him kill her son Vritra.[5]

Quote

I am Narayana, the Source of all things, the Eternal, the Unchangeable. I am the Creator of all things, and the Destroyer also of all. I am Vishnu, I am Brahma and I am Shankara, the chief of the gods. I am king Vaisravana, and I am Yama, the lord of the deceased spirits. I am Siva, I am Soma, and I am Kasyapa the lord of the created things. And, O best of regenerate ones, I am he called Dhatri, and he also that is called Vidhatri, and I am Sacrifice embodied. Fire is my mouth, the earth my feet, and the Sun and the Moon are my eyes; the Heaven is the crown of my head, the firmament and the cardinal points are my ears; the waters are born of my sweat. Space with the cardinal points are my body, and the Air is my mind...

...And, O Brahmana, whatever is obtained by men by the practice of truth, charity, ascetic austerities, and peace and harmlessness towards all creatures, and such other handsome deeds, is obtained because of my arrangements. Governed by my ordinance, men wander within my body, their senses overwhelmed by me. They move not according to their will but as they are moved by me.

— Mahabharata (translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, 1883-1896), Book 3, Varna Parva, Chapter CLXXXVIII (188)

Recent Posts

Recent Posts

[/url]

[/url]  [/url]

[/url]  [/url]

[/url]

to Bhujyu, and "raised (Rebha) up to see the sun" (úd…aírayataṃ svàr dṛśé, 1.112.5).[31][5]

to Bhujyu, and "raised (Rebha) up to see the sun" (úd…aírayataṃ svàr dṛśé, 1.112.5).[31][5]